A summary of the WWII events this day:

A summary of the WWII events this day:

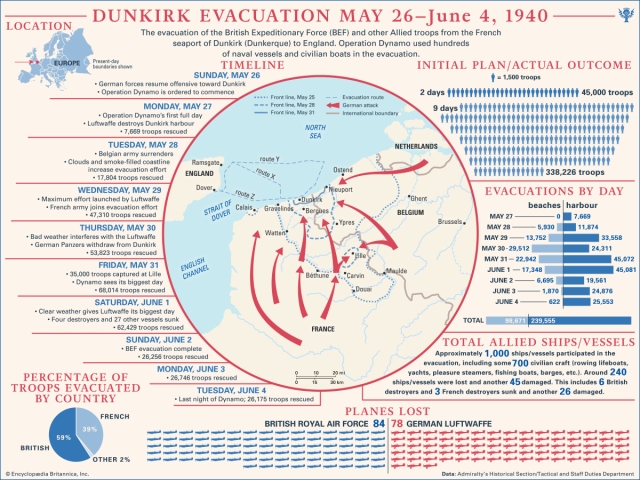

- Day 4 saw 53,823 evacuated from Dunkirk, with the total evacuees now at 126,606.

- Thanks to better discipline, the lorry jetties, and above all, the surge of little ships, the number of men lifted from the beaches rose from 13,752 on the 29th to 29,512 on the 30th, which offset the 9,000 drop from the harbours.

- Due to the heavy overcast skies, rescue fleets were able to stream across the Channel unchallenged by the Stukas and Heinkels.

- In the wake of the previous day’s losses, the British Admiralty ordered all modern destroyers to depart Dunkirk and leave 18 older destroyers to continue the evacuation.

- President Roosevelt rejected a request from US Ambassador to France William Bullitt, which asked for an American fleet to move into the Mediterranean Sea.

- Benito Mussolini advised Hitler that Italy was ready to enter the war.

- Three British battleships with £60 million in gold departed from Britain for Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.

- Germany increases food rations due to increased supplies from newly conquered countries.

BEF Commander Gort’s efforts to retreat to the coast had amazingly been executed. From Norman Gelb’s book, Dunkirk:

By nightfall of May 29, three days after its pilgrimage to the coast had begun, virtually all of the British Expeditionary Force had completed the trek. Except for stragglers, it had withdrawn into the Dunkirk perimeter. Paying a steep price in casualties, the troops holding the escape corridor open had done their job, and now the survivors among them had withdrawn as well. The desperate retreat had been carried out. But for most of the men, the great escape still appeared to be no more than a hope.

Men were dismayed by what they saw as they approached the end of their trek. From a distance, they beheld the pall of smoke from Dunkirk’s burning oil tanks….

…. to reach the beach, and see the mass of humanity there, all of them apparently with prior claim to evacuation, seemed another foretaste of doom. Those who had just been fighting the Germans knew the enemy advance guard couldn’t be far behind. And all had been under attack or threat of attack from German aircraft and knew their safety was still far from assured.

From Walter Lord’s book, The Miracle of Dunkirk; Churchill’s reaction to Gort’s decision not to leave:

One man absolutely determined not to leave was Commander Gort. The General’s decision became known in London on the morning of May 30, when Lord Munster arrived from the beaches. Winston Churchill was taking a bath at the time, but he could do business anywhere, and he summoned Munster for a tub-side chat. It was in this unlikely setting that Munster described Gort’s decision to stay to the end. He would never leave without specific orders.

Churchill was appalled at the thought. Why give Hitler the propaganda coup of capturing and displaying the British Commander-in-Chief? After discussing the matter with Eden, Dill, and Pownall, he wrote out in his own hand an order that left Gort no choice:

If we can still communicate we shall send you an order to return to England with such officers as you may choose at the moment when we deem your command so reduced that it can be handed over to a corps commander ….no personal discretion is left you in the matter.

As the logistical difficulties begin to be overcome, there appears a great surprise on the beaches. Again from Gelb’s book, Dunkirk:

…. A vast flotilla of small ships and boats, far more than had been there before, appeared off the coast. The methodical work of the Admiralty’s Small Vessels Pool and the requisitioning teams Ramsay had sent out was proving its worth. It was an extraordinary sight. All manner of small and medium-sized craft appeared — barges, train ferries, car ferries, passenger ferries, RAF launches, fishing smacks, tugs, motor-powered lifeboats, oar-propelled lifeboats, wherries, cockle boats, eel boats, picket boats, seaplane tenders. There were yachts and pleasure vessels of all kinds, some very expensive craft, some modest do-it-yourself conversions of ship’s lifeboats. There were Thames River excursion launches with rows of slatted seats and even a Thames River fire float.

They came from Portsmouth, Newhaven, Sheerness, Tilbury, Gravesend, Ramsgate, from all along England’s southern and southeastern coast, from ports big and small, from shipping towns and yachting harbors. Some, from upriver, had never been in the open sea before. They were manned mostly by volunteers, men who, without being given the details, had been told that they and their vessels were urgently needed to bring back soldiers from France. Most were experienced sailors — professional or otherwise — but many were fledglings who knew nothing about maritime hazards. Had the weather been bad, some would not have risked going; neither their experience nor their craft would have been up to it. Some mariners would forever be convinced that the extraordinary uncharacteristic calm which ruled the sea during most of the ten days of Dunkirk, permitting the evacuation to proceed — “the water was like a millpond” — was literally heaven-sent because “God had work for the British nation to do.”

Again from Lord’s book; Why the “millpond” conditions were more than needed:

Traveling in company, usually shepherded by an armed tug or skoot, the little ships moved across a smooth, gray carpet of sea. The English Channel has a reputation for nastiness, but it had behaved for four days now, and the calm continued on May 30. Best of all, there was a heavy mist, giving the Luftwaffe no chance to follow up the devastating raids of the 29th.

“Clouds so thick you can lean on them,” noted a Luftwaffe war diarist, as the Stukas and Heinkels remained grounded. At Fliegerkorps VIII General Major von Richthofen couldn’t believe it was that bad. At headquarters the sun was shining. He ordered Major Dinort, commanding the 2nd Stuka Squadron, to at least try an attack. Dinort took his planes up, but returned in ten minutes. Heavy fog over Dunkirk, he phoned headquarters. Exasperated, Richthofen countered that the day was certainly flyable where he was. If Herr General major didn’t believe him, Dinort shot back, just call the weather service.

But cloudy weather didn’t guarantee a safe passage for the little ships. Plenty of things could still go wrong. The Channel was full of nervous and inexperienced sailors.

…. [one boat] was almost run down by a destroyer that mistook her for a German S-boat. The skipper, Sub-Lieutenant Peter Bennett, managed to flash a recognition signal just in time. A little later he ran alongside an anchored French cargo ship, hoping to get some directions. “Où est l’armée britannique?” he called. The reply was a revolver shot. These were dangerous days for strangers asking questions.

Recap of our Road to Dunkirk:

- 1940.05.30 – The sea was like a millpond during days of Dunkirk. Almost 54,000 evacuated.

- 1940.05.29 – Glimmer of hope, Operation Dynamo succeeding beyond expectations.

- 1940.05.28 – Under Churchill’s leadership, UK commits to fight, unlike the French and Belgium governments.

- 1940.05.27 – Evacuation from Dunkirk begins with only 7,669 rescues, one-third of the total hoped for.

- 1940.05.26 – Operation Dynamo ordered to commence.

- 1940.05.25 – Port of Boulogne falls to the Germans.

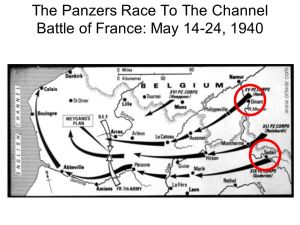

- 1940.05.24 – 400,000 Allied forces increasingly trapped towards the coast.

- 1940.05.23 – German Panzer Division drive towards the coast stops.

- 1940.05.22 – The Battle of Boulogne and the Siege of Calais began.

- 1940.05.21 – Planning for evacuation ramped up, but still no urgency.

- 1940.05.20 – London-based General Ironside, with Churchill’s approval, pushes BEF to attack towards the south.

- 1940.05.19 – London War Office fails to grasp degree to which British and French positions have deteriorated.

- 1940.05.18 – Belgium falls. British and French troops retreat north towards coast.

- 1940.05.17 – Churchill begins considering evacuating BEF troops from France.

- 1940.05.16 – BEF Commander Gort begins pulling troops back towards coast.

- 1940.05.15 – Churchill begins to realize that England might stand alone vs Nazi’s and continues his appeals to Roosevelt for US involvement.

- 1940.05.14 – The Blitz of Rotterdam [Belgium].

- 1940.05.10 – German Blitzkrieg begins into the *Low Countries and France. Cynics talk of Phoney War officially ends.

- *Also known as the Benelux Countries, aka Belgium, Netherlands [aka Holland] and Luxembourg.

- If it’s all Dutch [and/or Deutsch?] to you – here’s a great primer on how the varied country names came about.

- *Also known as the Benelux Countries, aka Belgium, Netherlands [aka Holland] and Luxembourg.

German Panzer Division drive towards the coast stops.

German Panzer Division drive towards the coast stops.

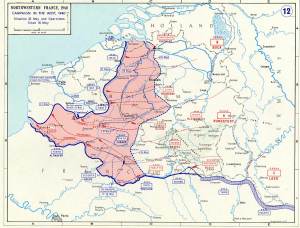

Following an enforced day of rest, the panzers were on the move again on May 22. Having reached the coast near St. Valéry two days earlier, they were now instructed to swing northeast toward the Channel ports. Resistance was patchy and disorganized, and by the evening they had reached the gates of both Boulogne and Calais. The next day, the 1st Panzer Division was moved from the gates of Calais to attack the British toward the line of the Aa Canal to the east, and the 10th Panzer Division was brought in to mop up the defenders of the famous old port.

Following an enforced day of rest, the panzers were on the move again on May 22. Having reached the coast near St. Valéry two days earlier, they were now instructed to swing northeast toward the Channel ports. Resistance was patchy and disorganized, and by the evening they had reached the gates of both Boulogne and Calais. The next day, the 1st Panzer Division was moved from the gates of Calais to attack the British toward the line of the Aa Canal to the east, and the 10th Panzer Division was brought in to mop up the defenders of the famous old port. A summary of the WWII events

A summary of the WWII events